Simplicity to a Fault: Springsteen's Wrecking Ball

Some of the greatest rock and roll songs ever have also been the simplest. Whether you’re a fan of Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly, The Clash and The Ramones or Green Day and Nirvana, sometimes the simplest songs capture emotions with a charge unattainable by more complex arrangements. Are you telling me that “Baba O’Riley” doesn’t still give you chills? Come on.

In two weeks, I’m attending my first Bruce Springsteen show in thirteen years, this time with my fifteen year-old daughter. In preparation, I thought it made sense to purchase The Boss’s latest effort, Wrecking Ball, but while digesting the material over the past few months, I keep coming to the same conclusion: the album is simplistic to a fault. There isn’t a chord or a note on the entire album that surprises me, that gives me pause or a reason to take notice. By track six, I’m so bored, I inevitably turn it off and wait to digest the final five songs at a later listening session.

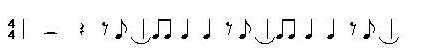

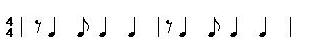

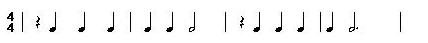

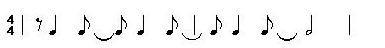

To confirm my instincts, I tracked the chord changes of each song on the eleven-track album. Here are the results:

- Every song is in a major key.

- Not one song changes key.

- Every song but one is in 4/4, with an occasional 2/4 measure thrown in.

- On the entire album, there are a total of five chords, with an occasional altered root note: I, IV, V, vi minor and ii minor. That’s it. And the ii minor chord only appears on one song, so 10 songs have at most four chords in them.

Now, I’m not dissing simplicity. Give me a good Johnny Cash album or Green Day album or classic Stones album, and I’m a happy guy. But Springsteen’s latest album is nothing short of a bore. Just as Yes and Genesis became too complex for their own good in the 1970s, Springsteen has become so simple that there isn’t any reason for listeners to care.

One could counter my conclusion by saying that Springsteen has always been simple, so why start complaining now?

But it wasn’t always this way.

Take a song like “Hungry Heart.” Simple? Yes. But what really makes the song work is the unexpected key change leading into the organ solo, and then changing keys again for the final verse. Nothing fancy, but just enough alteration to make the listener take notice. The song “Born to Run” is also a relatively simply song (though the chorus alone contains more chords than the entire Wrecking Ball album), but what really lifts the song from good to great is the interlude that contains an odd key change, a chromatic descension and a four measure pause before resolving back to the one chord in an achingly satisfying way.

So much of Springsteen’s new album could have benefitted from a bridge with a different chord, a key change, a pause, a tempo or meter change, a something. Tracks like “Wrecking Ball,” “Shackled and Drawn,” “We Take Care of our Own” are fine for a while, but listen to them successively and sleepiness sets in.

I’ve no doubt that hearing “Death to my Hometown” or “Easy Money” will be great fun when shared with 40,000 fans come September 8th, but I’m afraid that after the Wrigley Field concert, Wrecking Ball will no longer make it into my regular rotation.

(I should note that “Land of Hope and Dreams,” which appears in studio form for the first time on this album, is on par with Springsteen’s greatest songs ever. As I said, sometimes simple is good.)