Deceptive Downbeats (reprised)

On Adam Neely’s latest video (fantastic, as always), he discusses something called “post-facto metric ambiguity,” a fancy term that I’ve written about previously, albeit under a different term: deceptive downbeats. It’s a way to describe a musical passage – often at the beginning of a piece – that’s difficult to rhythmically understand until a downbeat is established. I love this stuff, and there are a bunch of tunes that trip me up even after I know the “correct” way of hearing them. Neely addressed the intro to The Beatles’ classic, “Drive My Car,” and it’s one of many examples one can turn to. I definitely recommend Adam’s video (and his channel in general) and have copied below my original blog on the subject matter, written almost exactly ten years ago.

Deceptive Downbeats (a musical observation)

When listening to music, there’s nothing quite so satisfying as a surprise: a harmony that doesn’t resolve as expected, a lyric that takes a comedic twist or a melody that jumps an odd interval away.

What excites me the most (and what lays to rest any question of my geekdom) is a rhythm that doesn’t change time signatures, but that still manages to fake the listener out, intentionally or not, by calling the downbeat into question. In this scenario, what you initially hear as the “one” beat you come to find is someplace else entirely, and your ears are left to add or subtract a beat or a half a beat in order to get back in synch with a song, like dancing to a CD that skips and having to make an adjustment before you step on your partner’s toes.

My favorite example occurs in the Yes song, “Yours is no Disgrace." For over three decades I’ve never failed to hear the first chord as landing on the “and” of four in a 4/4 measure. Give a listen:

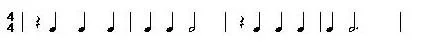

I hear the song as:

But once the band kicks in, it sounds like Yes has subtracted a beat, inserting a measure of 3/4 instead of 4/4 (and with Yes, this is an entirely plausible proposition). In truth, the time signature remains constant for this part of the song, but my ears hear the downbeat incorrectly. The first note lands on the “and” of one, not four:

Even with this knowledge, I still hear the rhythm the way I always have, and after thirty years (note: now forty!), I guess I kind of like it that way.

Another example is Sting’s “Ghost Story.” This song starts similarly, with an instrumental passage absent an obvious count-in. But even when Sting’s voice enters, the downbeat is in question:

I’ve always heard first note coming on beat two of a 4/4 measure:

But as soon as Sting sings “Another winter comes, his icy fingers creep,” a half a beat is added, and it become clear that all along the initial note of each phrase had in fact landed on the “and” of one:

Sting uses this deceptive tactic often, though I suspect in his mind there’s nothing deceptive about it since he hears the downbeat where it should be, and there are probably many listeners who hear it correctly right off the bat. But to me, my faulty instincts add to the pleasure of the song, providing just enough jolt to keep things interesting.

AN ADDENDUM: I was going to add a “part two” to this idea many years ago and never did, but there are a few more examples I can think of off the top of my head:

The piano that begins the outro of Supertramp’s “Crime of the Century.”

The intro to “Start Me Up” by the Rolling Stones.

The intro to “Fortress Around Your Heart” by Sting.

Great stuff! Shoot me a message if you’ve got some other examples.